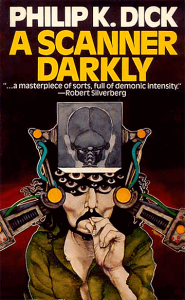

Dick, Philip K. (Doubleday, 1977, ISBN 0385016131)

My grandfather bought the Volkswagen in 1968. He imported it direct from Germany and shifted the steering column over to the right-hand side.

A year later man set foot on the moon.

Twenty-eight years later, in 1997, my grandparents sold the Volkswagen to my brother and me for $400.

I speculate that the original registration document had described the colour as beige. By the time we got the car, it had no colour in particular. Instead, it registered in your thoughts like an object whose colour lies hidden behind dust. Your brain refused to assign it a definite colour until someone cleared off some of the dust.

Inside, it had vinyl seats stuffed with straw and supported by rusty springs that sometimes forced their way through the vinyl. The biggest split ran along the top of the passenger seat. The stuffing had come out, leaving a curving guillotine of metal that ran behind the passenger’s neck.

The Volkswagen used an eccentric transmission scheme the manual called, ‘auto-stick semi-manual transmission’. Instead of a clutch pedal, moving the gear stick a little (or touching it or bumping it) opened the clutch. To put it into reverse you moved the stick to neutral, pushed it down towards the floor, rolled it clockwise around the perimeter of an imaginary semicircle and then jerked it straight back towards the rear of the car. To put it back, you pushed it forward, swung it back round the semicircle and then let it pop back up into neutral.

Despite more than two hundred thousand kilometres on the road, when we got the car it had a plethora of quirks but no major mechanical problems. Over the next seven years, I ran it into the ground.

First it started to stall – most often when turning through a busy intersection. Then, it became hard to start – or restart, for instance after it had stalled while turning through a busy intersection. I discovered that drivers in Melbourne will honk a stalled car that blocks them, as if you possessed the ability to get your car out of their way and just needed them to tell you to use it. Did they think that you’d stopped there on purpose and just needed their encouragement to start moving again? Putting this question to them, I discovered two things:

- Few people will conduct a rational conversation with a man who gets out of his car in traffic and goes over to talk to them at their car.

- Melbourne’s motorist sees his horn, not as a device he can use to warn or urge on other motorists, but as a disintegration ray he can use to disintegrate any obstacles that get in his path.

After a few years, the Volkswagen’s horn started to fire off at random. It seemed to happen more often while turning to the right. I warned the helpless passengers ahead of time, but few believed it until they’d seen it happen. I too found it hard to believe that anything could connect a car’s steering to its horn, but we couldn’t deny that any abrupt turn to the right stood an excellent change of triggering it. I pictured it as a geriatric problem. Like a swollen prostate gland that puts pressure on the bladder, I imagined that something in the steering had fallen out of place and run up against the horn’s air reserve.

More to my alarm, the car’s accelerator started to get stuck down. Six times a year I had the accident that almost kills the characters in A Scanner Darkly. As I pressed down on the pedal, back in the engine the return spring on the accelerator cable would pop off. As I lifted my foot, the pedal stayed down, the engine revved up to its maximum and the car continued to accelerate.

Your instincts in this situation urge you to turn off the ignition.

Wrong.

In a Volkswagen 1200, turning off the ignition locks the steering. Now you find yourself going eighty kilometres an hour in a straight line, in a pre-moon landing Volkswagen with an incontinent horn that will not start. Instead, I learned to put the car into neutral, ignore the shriek from an engine revving at full in neutral and look for somewhere to park.

Over the seven years, the Volkswagen broke down maybe fifty times. I pushed it kilometres (on occasion with the help of the people whose tram or hospital it blocked). I learned where to find the box numbers on freeway emergency phones located along the emergency lane.

At last, with thirty-six years and three hundred thousand kilometres behind it, the Volkswagen broke down for good in 2004 at the intersection of Orrong Road and the Princes Highway. Finding ourselves halfway through the intersection, in heavy traffic, the passenger and I pushed it up on to a road island – “Volkswagen Island” – where we abandoned it so I could make the usual calls to city councils and see if a mechanic could resurrect it one more time.

It stayed on that road island for a week before I had the money to have anyone tow it. Friends of mine who passed it telephoned to see if I’d fallen into trouble.

The Volkswagen never started again. A week later, the tow truck dropped it at my parents’ house, who found a way to dispose of it. I’d won. I’d killed the Volkswagen before it killed me.

Oh my god. Hilarious and worrying. Though your spelling of “Volkswagen” changes through the article. The “wagen”, rather than “wagon”, is correct. Of course if Volkswagon was the nickname of the car, that’s fine too.

Oh! I’ll fix it…

That is just terrifying.

Pingback: Carnegie Valet | Melbourne Review of Books

Pingback: Flat Inspection | Melbourne Review of Books

Pingback: Igloo | Melbourne Review of Books

Pingback: Clearwater Primeval | Melbourne Review of Books

Pingback: Motoring | Melbourne Review of Books

Pingback: Domain Tunnel | The Melbourne Review of Books

Pingback: Crescendo to an error | The Melbourne Review of Books

Such a deep anserw! GD&RVVF