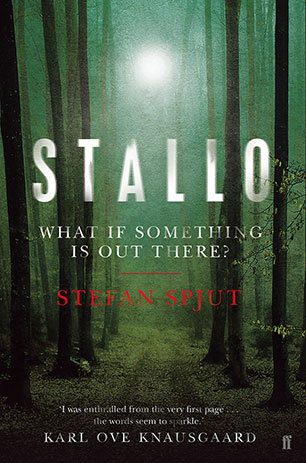

STALLO

STALLO

Faber/Allen & Unwin, RRP $29.99

July 2015

Imagine, if you will, a scene: a crowd of sports fans shocked into silence. A bobsled overturned oh-so-close to the end of the track. Four plucky Jamaicans crawl unharmed out of their upended bobsled, their hopes and dreams for Olympic glory shattered. But what’s this? They’re picking up the bobsled. I don’t believe it! They’re picking it up and now they are carrying it. These crazy guys are going to get to that damn finish line by hook or by crook. It’s time people. Can you feel it? The air is buzzing with it. It’s perfect. Someone in the crowd feels it and they’ve started it—the slow clap. It builds, slowly of course, as more and more people join in. It soon becomes a joyous crescendo and the crowd goes wild, spurring on our heroes to reach their poignant but ultimately pointless goal.

This is my odd little way of introducing Stallo, by Stefan Spjut. While there are no bobsleds, no Jamaicans and certainly no John Candy, there is a lot of snow, a lot of snus and a lot of build up. Slowly (at 600 or so pages) and surely, it starts strong and loud and builds speed to become a crashing cacophony.

From the unsettling slightly blurred font on the cover page to the disturbing and rather melancholy climax, Stallo is a strange and creeping mystery that travels nigh on the entire length of Sweden. It evokes the cold chill of a Scandinavian winter, lonely cabins in darkened woods, and the great unknown of the aurora-lit north and Lappland. And it is from Lappland and the Sami that we get the title, Stallo, for troll-like beings.

The novel begins with a shot back in time to 1978 when Magnus Brodin and his mother are on a holiday in a cabin in the woods.* After a series of strange happenings, Magnus is taken in the eeriest of circumstances by, as his mother sees it, a giant. Leaping forward 25 years and the book takes on two storylines. Susso Myrén runs a cryptozoological website that looks for evidence of all the oogedy-boogedy things that people like to search for—Nessie, Bigfoot, you know the score. But Susso’s interest is a little more specific: trolls. Her grandfather Gunnar was known for an aerial photograph he took in 1977 of a bear with a humanoid creature riding on its back. After hearing from a woman who had seen a strange person staring into her home at her and her grandson, Matthias, Susso sets up her wildlife camera outside the woman’s home. When Matthias is kidnapped, Susso’s time lapse photos of a small, strange looking person is quite possibly the only clue to his disappearance, and possibly the only clue that may lead to finding him.

For Seved and his motley “family” however, their survival may hinge on stopping Susso from finding them and Matthias. The boy they had to take to keep them entertained, the “old-timers” and the shape-shifters their entire lives revolve around.

If we’re going to attach meaningless labels onto things, I could say Stallo was a cryptozoological supernatural mystery—if for no other reason than to be able to say cryptozoological. I have previously stated my thoughts on the existence of trolls but in case you missed it: they exist and you won’t convince me otherwise despite there being no empirical evidence that they do indeed exist. Still I place the burden of proof on you.

The book flits between third person narration for Susso and Torbjörn (Susso’s ex-boyfriend and new step-brother) and for the troll keepers as I shall dub them, and first person for Gudrun, Susso’s mother. It is when Gudrun, Susso and Torbjörn head off on a road trip following clues to the whereabouts of the little person in the photos that the slow clap crescendo starts picking up speed. And while the Myrén posse are on their detective mission, Seved must face the realisation of who he is and what has happened to him through the eyes of Matthias, the boy stolen on his way home from grandmother’s house like some gender-bent Red Riding Hood tale.

Stallo blends a quiet sadness with the small mundanities of life and disturbing themes, both visceral and mental. There is however something in a translated work that we need to take on trust and that is the translator’s ability to capture the essence of the language as well as the story. It is something I attend to when reading something translated in a tongue I am familiar with. Sometimes something catches like a hangnail on a stocking and there’s that feeling of needing to wave one’s arms about and yell, no, you’re missing out on the fuller meaning of this phrase or that. Sadly I cannot read Swedish other than to make some—I flatter myself—pretty good headway into getting the general gist. And so I must have faith that Susan Beard has risen to the difficult art of transferring time, place and culture from Swedish to English.

For those who only like clear resolutions, Stallo is a long read that may not satisfy. But for those that like to be swept along by a story that leaves you to your own conclusions, it is well worth reading this hefty tome.

*What could possibly go wrong?