Serpent's Tail

2006

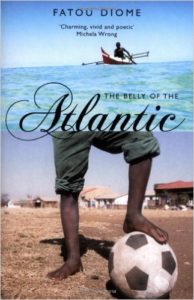

Fatou Diome’s The Belly of the Atlantic is a passionate story about the dream of migration and its harsh reality. Told from the point of view of Strasbourg resident Salie, the novel nonetheless focuses mostly on her brother Madické. Madické lives on the Senegalese island Niodior and dreams of being headhunted to join a big European soccer team. This dream is shared by many of his friends, persisting despite the warnings of Salie and the teacher Ndétare that neither the road to nor the life in Europe is as good as they believe.

Fatou Diome’s The Belly of the Atlantic is a passionate story about the dream of migration and its harsh reality. Told from the point of view of Strasbourg resident Salie, the novel nonetheless focuses mostly on her brother Madické. Madické lives on the Senegalese island Niodior and dreams of being headhunted to join a big European soccer team. This dream is shared by many of his friends, persisting despite the warnings of Salie and the teacher Ndétare that neither the road to nor the life in Europe is as good as they believe.

Little detail is given of Salie’s life in France or how she came to live there in the first place. The reasons for her departure are eventually revealed, and the means of her arrival on a temporary visa, but we know little about her daily life. This seems strange, but it helps the thematic elements of the story as well as expressing Diome’s knowledge of her audience. After all, Diome is herself a Senegalese-born Frenchwoman. The novel was originally written in French for a French audience, and including an audience of other migrants who would be familiar with the sorts of experiences Salie has had. Moreover it highlights the anonymity of the migrant; the loss of story and identity as one is subsumed into an “other”.

Niodior on the other hand is full of stories. Salie relates stories from her past and stories she’s heard, of the island and of people who left the island, many of whom returned. She undercuts the supposedly successful adventures of the man who owns the only television on the island, for example. And the risks of human traffickers maskerading as soccer club scouts are revealed through the story of Moussa. There are rumours that have become almost legend concerning island characters who bore illegitimate children or otherwise breached the strictures of Senegelese propriety. Diome does not romanticise life on Niodior; it is impoverished and oppressive.

Diome handles her various themes ably. Since there are a lot of themes, encompassing a broad array of experiences and concepts, this is a solid achievement. Diome has packed a lot of consideration into a relatively short novel, and readers will have a lot to think about in reading.

Not being much of a soccer fan, much of the discussion about it went over my head, but this did not come at the cost of the story. What I did find more bothersome was the occasionally overlong rants that Salie goes on in her mind. I don’t know whether this is a stylistic choice or a literary tradition of either France or Senegal, but at least in translation some of them came across as trite. They contain important messages about colonialism, capitalism, racism and migration policy, amongst other things. These are topics deserving of consideration and clearly central themes, but could have been conveyed more effectively with less bombast. Some other passages also jump out as rather overwritten, but I wonder how much of this is because of the translation.

Another difficulty I had was with occasional balks in the translated copy. There were some occasions of odd, even incomprihensible syntax. The blurb on the 2006 edition is misleading and accurate from its first sentence, “Salie lives in Paris”. This is obviously not a fault of Diome so much as the translators, printers and editors behind the English addition. Unfortunately, this may prevent non-French readers from enjoying this interesting and (mostly) poetically written book.