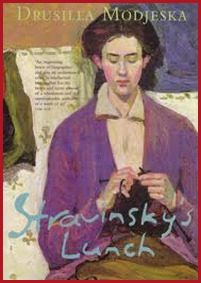

Drusilla Modjeska ISBN 0 330 36186 4

Amongst ordinary things, among cups and saucers, couples chatting in a courtyard, trees, the expression on a face, there may also be questions about what one sees, and what it means. For the artist, these questions might be about Life, they might be about Love, they might be about Art, and the way in which a person may—but here is the tension—live and love and create.

In Stravinsky’s Lunch Drusilla Mojeska recalls a dinner party with friends, and a kernel of a story shared: simply, when Igor Stravinsky was mid-composition, he insisted that his family ate lunch in silence. A male friend present at Modjeska’s party reasoned that ‘art, if it is to be Art, must win out’—genius, of course, demanded exacting conditions to carry out its work. Other women countered that it might be reasonable for Stravinsky to impose this restriction on himself, but not upon others at the table. He could have eaten off a tray in his study. A maid could even have carried it.

The debate, which ‘spilled over’ into their lives, reveals the gendered nature of the tension between Life and Art. Creating art requires space, time and money, a fact popularised by Virginia Wolf in her essay A Room of One’s Own. The status of art in a woman’s life may determine how often she puts down her obligations and goes to her work room, if she has one. In 1999 when Stravinsky’s Lunch was first published the gendered threads of this debate were obviously alive—I would argue that they still are.

Mojeska meditates upon the story of Stravinsky’s lunch while she goes on to set down the artistic biographies of two painters, Stella Bowen, born in Adelaide, 1893, and Grace Cossington Smith, born in Sydney, 1892. Bowen travelled abroad to Europe as a young adult, was held there by World War I, fell in love with author Ford Maddox Ford, with whom she had a daughter and lived with until their separation and the period of freedom and financial pressure before her death. Smith was born into a North Shore family, never married, and lived out her days painting in her private studio.

The ‘bohemian and the spinster’ as Mojeska characterises them, and to NY Times reviewer Stacey Schiff (2000), Smith certainly had ‘no domestic life to speak of’ with no one to ‘disturb her at mealtimes’. It is not quite true: Smith lived with her sister in their family home until her sister’s death. This strikes me as a sweeping aside of the interior life of the woman who painted what are now recognised as illuminating works of art, works that see through. Smith said that she simply ‘paints what [she] sees’.

Schiff also took exception to the multiple questions Modjeska lays down in the Smith section (she counts 20 on page 213, she says) suggesting this reveals the weakness of a pilot lost. Modjeska is a careful researcher, and while 20 questions might be unsettling, they speak into the absence of a woman whose interior life was not written down; the questions are part of the unknowability of Smith’s story, and questions form part of Bowen’s story also. Whilst Bowen published an elegant biography Drawn from Life, which is quoted throughout, Grace speaks only through fragments of interviews given late in life, and some preserved letters. Bowen received a commission from the Australian War Memorial as a war artist during World War II. Smith exhibited but some of her most celebrated paintings lay in her studio for decades. She did not speak because for much of the time no one was interested.

A second meditative theme Modjeska gives us is Rilke’s poem about Paula Modersohn-Becker: bowls of fruit… you let yourself inside / down to your gaze; which stayed in front, immense, / and didn’t say: I am that; no: this is. Rilke’s understanding of early modernist artist Modersohn-Becker’s work came only after her early death, and amounts to her steady gaze at the substance of things as they are, their contradictions and dualities, the pull between Art and Life, between Love and Art, and taking it all in, leaves nothing out. She does not identify herself as an other, simply she shows herself bare, ‘no: this is’. In this way, Modjeska decides for Smith ‘there is no separation. There is no dilemma’. Stella, similarly to Modersohn-Becker, managed to realise ‘there are ways of being in the world that allow us, in the same breath, to live in our domestic ordinariness and still create’.

Modjeska’s commentary of the paintings is illuminating for the reader like myself who has never known how one could speak about painting. The paintings themselves are a treat. Stravinksy’s Lunch is still a relevant and compulsively readable take on two elusive figures in Australian art.