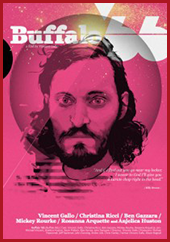

I revere Vincent Gallo’s film Buffalo 66 as a work of genius. From the outset, the film seizes our attention through its humour and stunning photography. Buffalo looks like Orwell’s bright cold day in April when the clocks struck thirteen. Gallo’s flurrying delivery leaves us in hysterics.

At first, we despise his protagonist. After heckling her away from the

payphone, Billy mooches phone change from the tap dancer and then sneers at her in return.

“Don’t you say thanks?”

“What?”

“Don’t you say, ‘thank you’?”

“What?”

In the toilets, he all but beats a man in a tantrum of homophobia.

At best, we see him as a rodent trying to swagger like the eagle.

And then, somewhere between the train wreck of his family and his friend Goon who sent the raisins, we start to feel sorry for him. By the time we finish cackling at the photo-booth snapshots of the couple “spanning time together” and the goal kicker’s “Sexxotic dancers”, we discover that we’ve come to care about him. We even like him. As he treads the last footsteps of his plan for vengeance, we pray that he’ll turn back.

How did we come to care about Billy Brown?

In 2003, news reached me that Gallo’s newest film would debut at the Melbourne Underground Film Festival. I mustered a posse to see it.

Before the screening, the film’s co-writer and co-director, Dale Reeves, welcomed us to the theatre, apologising that Gallo couldn’t make it tonight. Dale had a bodybuilder’s body but pudgy cheeks and a weighty head that he waxed bare. Together, it generated the impression of a giant baby forced into a suit. Dale stammered through a swift speech, relating how for years, he’d dreamed of making this film. At last, after years of striving, his dream had become reality.

As we applauded, he beamed at us in thanks and tears welled in his eyes. It seemed a moment of perfect joy.

Dale moved to the back of the cinema near the door. We sat in the backmost row over to one side of him. Most of the other seats remained tenantless. Leaving out people connected to the film or festival, it appeared that less than a dozen patrons had come to see it.

In the end, Vincent Gallo’s 2003 film The Brown Bunny suffered from its premature release. Or so I gathered later; we never saw it. Instead, by mistake, we had gone to see Vin-cenzo Gallo’s Nightclubber, which suffered from a total lack of any merit.

It resembled nothing so much as a teenaged boy’s attempt at self-aggrandisement. It starred Dale Reeves himself (at that moment standing behind and to the right of us) in the role of ‘NC’, following NC’s quest to prove to the wincing viewer what a badass he’d become.

The majority of the dialogue sounded like that same teenager browbeaten by a relative into describing his day at school. The remainder they had derived from a farrago of 80s action movies and rock albums, divested of any lingering humour and then subjected to several rounds of machine translation.

Though I now find it amusing to recollect, at the time it produced in us an amalgam of embarrassment and loathing akin to seeing a man soil himself in public. We felt an overpowering need to get away from it, but we could only gain the exit by trampling through a man’s dreams.

When, at the Last Judgement, the matter of my atheism comes before the celestial court, my attorney (if he knows his stuff) will cite my endurance on this occasion as evidence of my good character. He will summon witnesses present on that evening to testify that, with my comrades, I held to my seat for a full thirty minutes.

However, under cross-examination, I fear that the suave prosecutor may force me to admit that this constituted less than a third of the film’s full length. Or that (“more damning still,” I can hear him chuckling to the jury) for the last ten of those minutes, rather than hanging on out of any laudable sympathy, we simply lacked the nerve to shuffle out of the theatre two feet in front of the man’s nose.