Picador

May 2015

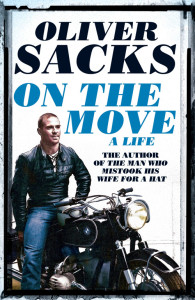

The way other people see us isn’t necessarily the way we see ourselves. This was my first impression of Oliver Sacks, eminent neurologist, when seeing the cover of his memoir On The Move. Rather than providing a photo of himself as a distinguished older gentleman at the end of a distinguished neurological career, what we get instead is Sacks, virile, young, muscular, and leather-clad, astride a motorcycle. This is the Oliver Sacks that he wants us to remember, the inner Sacks that perhaps people had began to forget but he never had. There’s a fondness for the adventure of youth before the pages even open, and I found myself needing to recalibrate to the idea that perhaps this wasn’t the story of dogged academic pursuit after all.

The way other people see us isn’t necessarily the way we see ourselves. This was my first impression of Oliver Sacks, eminent neurologist, when seeing the cover of his memoir On The Move. Rather than providing a photo of himself as a distinguished older gentleman at the end of a distinguished neurological career, what we get instead is Sacks, virile, young, muscular, and leather-clad, astride a motorcycle. This is the Oliver Sacks that he wants us to remember, the inner Sacks that perhaps people had began to forget but he never had. There’s a fondness for the adventure of youth before the pages even open, and I found myself needing to recalibrate to the idea that perhaps this wasn’t the story of dogged academic pursuit after all.

In fact, Sacks career in medicine was initially a reluctant one. He came from a family of doctors, so when it was time, off to medical school he went. Despite achieving a full academic scholarship to Oxford, it took him four attempts at the entry exam before he managed a pass. While incredibly bright, Sacks was not particularly suited to rules and standardised knowledge; a tendency that would create obstacles throughout his early career, but would also allow him great insight in his later clinical work.

But those years of medical school are largely a blur in the writing of On The Move. The years of internship and residency in California sweep by. Instead, during those same years, we see the other life of Oliver Sacks, in a sense the real person behind the imposed expectations of familial obligation. Sacks revelled in what many would consider a decedent lifestyle, especially in the 1950s and 60s; motorbikes, experimental drugs and anonymous sex. And yet it’s more self-discovery than self-destruction. We start to see the person that Sacks saw himself to be; in his side trips to pristine mountain ranges with glimmering lakes, or desolate desertscapes in America. In these in-between places, he wrote furiously and poetically on the beauty of nature while pining for the possibility of a life with just the open road and inspiration.

It’s these chapters where Sacks really comes alive. Each phase of his life, every encounter, is transformed by his vivid recollection of the people that shared it with him. His is a life shaped by connection to others, and a sincere passion for the quirks and foibles that make us human. The young men of early Sacks’s life, both friends and lovers, are treated with the tenderness of loyalty and devotion, and memories fondly held. But there comes a point in Sacks’s story where the journey of youth and adventure ends, and his clinical work takes over.

Whole-heartedly takes over; at one point Sacks lives in an apartment in Beth Abraham hospital so that he can be permanently on call for his patients. And while, perhaps, this is the main show, Oliver Sacks’s eminent career, the story starts to slow at this point. Some of Sacks’s fire has settled, no doubt the combination of a drug scare too far, a sequence of unrequited loves, and the approach of middle age. It’s during this time that Sacks bucks the conventions of typical medical research and instead tells the story of his patients in only the way he can, and in so doing he captures the world. And yet, throughout all of this, his life feels a little less bright than it was in youth, at least until he finds love again in his 80s. What’s clear is that love makes him young all over again.

Oliver Sacks might not have wanted to become a doctor and neurologist, but the world is a brighter, better, and more enlightened place for it. He didn’t choose his path, but he made it his own. And he made sure to have adventures along the way. Maybe that’s the final lesson he wanted to leave us with. It may fall to you to be this or that profession, and it may not be your first choice. But wherever you land in life, you can find a way to make it your own and bring your own brilliant flame.