J. R. R. and Christopher Tolkien

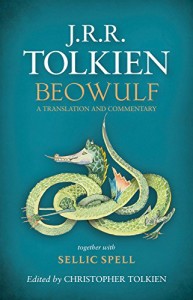

Mariner Books, August 2015

A thousand years on, the sharpness of Beowulf‘s images still strikes us. Longships cruise amid icy spray. A king stares with fear amid the riches of his hall. Then comes the fiend Grendel stalking across the moors. Tolkien’s translation weds to these visions the rhythm and grandeur of language that rumbles even as it exults, which rolls like the swells of the sea.

But in that time, the narrative art has matured. It has not just adapted to modern environments and habits of thought; it has made bona fide progress of a sort that I believe the ancient storyteller would recognize. Of late, it has come to realize that before it can sway the reader, it must first fight off other challengers for his or her attention. Modern audiences expect certain basics from the adventure story:

(•) Heroes will have flaws. At a minimum, their aptitude in certain domains will seem untested. If the hero excels at violence, we will wonder how he will fare at court. If he has the strength of a lion, he may have the brains of a sparrow. If he has the diligence of a German, he may have the manners of an American. If, on the contrary, the audience accepts our hero from the start as equal to anything fate may throw his or her way, what suspense can they feel?

(•) The plot will have twists. At a minimum, unexpected complications will ensue. If the audience can chart the plot’s course in advance, then another avenue for their curiosity has closed off.

(•) The story will not enumerate long lists of ancestors who contribute nothing to the plot.

(•) Nor will it take periodic breaks from the action to harangue the reader with long, delusional tirades about the benevolence of God.

The audience of Beowulf‘s day no doubt found that it met their narrative needs. Those same elements that a modern audience would decry, an ancient one may’ve deemed essential. For all I know, no skop worth his mead would even flirt with the idea of singing his tale without first listing off its characters’ ancestors.

However, one struggles to see how his modern counterpart could get the thing past an editor, much less a seasoned workshop group. Imagine its members’ satisfaction as they bury it beneath their complaints. The first member will say that readers won’t have the patience to read such “complicated” sentences, by which it will develop he means any line that would sound out of place in a young-adult novel or comic book.

The second will insist that ‘warlike shields’, ‘shafted spears’, ‘builded hall’ and many similar expressions constitute unforgiveable tautologies (whether they fit the meter or not).

A third will contend that the story Beowulf ought to start with the character Beowulf (which she will call its “eponymous hero”) or at least place him among the first few introduced. Why, she’ll ask, does the story wait, even to introduce him as an unnamed knight of the Geats, until it has already introduced Scyld, Healfdene the High, Heorogar, Hrothgar, Halga the Good, Healfdene’s daughter, Scylfing, Grendel and another, different prince also named ‘Beowulf’ (not to mention Cain and Abel, unnamed comrades and vassals, the personified ocean and sixteen references to God)?

Another member will point out that Beowulf’s huge physical strength, rather than enhancing his heroism, acts to diminish it instead. Beowulf has the strength of thirty men. If we admire Beowulf’s courage when he confronts Grendel, our member asks, how much more must we admire the courage of those lesser knights who dared to face that bloodstained monster with just one-thirtieth of Beowulf’s strength?

Beowulf risks his life when he faces first Grendel, then Grendel’s Dam and at last the dragon who kills him. But in light of his physical strength, that member reminds us, he takes no more risk than any warrior takes in battle.

Between Grendel’s mother and the dragon, Beowulf also fights other warriors. What will the reader think, our member asks, of a man who takes to the field of battle against creatures possessing one-thirtieth of his own strength?

Other workshop members may tackle the story’s constant “telling” of its characters’ virtues that accompanies their “showing”.

They may wonder about the curious disconnection between the earlier episodes and Beowulf’s later fight with the dragon.

They may criticize the one-sidedness of the story’s antagonists (Unferth and the monsters alike).

They may complain that it fails to make us like its boasting glory-hound of a hero, though we may sympathize with Grendel’s mum.

And yet one might level many of the same complaints against Siegfried, The Raven, Henry VIII or Aguirra, the Wrath of God.

The current edition of the book runs a preface and separate introduction to the translation by Tolkien’s son Christopher before the main feature.

After that come Christopher’s “Notes on the Text of the Translation” and “Introductory Note to the Commentary”. They cover in detail the intricate history of corrections and emendations to individual words and phrases in his father’s manuscripts.

After these follow two-hundred pages of J. R. R. Tolkien’s line-by-line comments on his translation choices.

Next come two different English revisions of Tolkien’s Sellic Spell: a retelling of Beowulf, which again feature introductions by Christopher.

Sellic Spell retains the original setting of dark-ages warriors and monsters beheading one another in the snow. One can’t blame the author, but after three-hundred pages of such business, one wonders if the reader might’ve welcomed something contemporary instead. Imagine the residents of Heorot, South Australia brought to ruin by the Grendel Hydraulic Fracturing Company. They attempt legal challenges, but one by one Grendel Co. vanquish their attorneys in court. Grendel Co. defeat thirty plaintiffs in a single class action. At last, Queen’s Council Jack Beowulf from Victoria takes their case. They say he knows the legal skullduggery of thirty barristers. He vanquishes Grendel Co., then later its parent company, before retiring to Bendigo.

After the English versions comes an Old English version of Sellic Spell (with a further introduction by Christopher).

Last follow two revisions of Tolkien’s The Lay of Beowulf: a retelling of Beowulf in verse, again with an introduction by Christopher.

Last Monday, I emailed Christopher Tolkien through his solicitor Cathleen Blackburn to see if he would write an introduction to our review. So far I haven’t heard anything back.

Excerpts:

“He overmatched thee in swimming, he had greater strength! Then on the morrow-tide the billows bore him up away to the Heathoreamas’ land; whence he beloved of his people, sought his own dear soil, the land of Brandings and his fair stronghold, where a folk he ruled, his strong town and his rings.”

“Voyagers by sea, such as have borne gifts and treasures for the Geats thither in token of good will, have since reported that he hath in the grasp of his hand the might and power of thirty men, valiant in battle.”

“Foul thief, he purposed of the race of men someone to snare within that lofty hall.”

“Now, Beowulf, best of men, I will cherish thee in my heart even as a son; hereafter keep thou well this new kinship. Lack shall thou have of none of they desires in the world, of such as lie in my power. Full oft for less have I granted a reward and honourable gifts from my treasure to a humbler man and to one less eager in battle. Thou hast achieved for thyself with thine own deeds that thy glory shall life forever to all ages. The Almighty reward thee with good, even as He hitherto hath done!”

“In no wise had they joy in that banqueting, foul doers of ill deeds, that they should devour me sitting round in feast night to the bottoms of the sea; nay, upon the morrow they lay upon the shore in the flotsam of the waves, wounded with sword-thrusts, by blades done to death, so that never thereafter might they about the steep straits molest the passage of seafaring men.”

“Thence back he got him gloating over his prey, faring homeward with his glut of murder to seek his lairs.”

“To the abyss drew me a destroying foe accurséd, fast the grim thing held me in its gripe”

“At times they vowed sacrifices to idols in their heathen tabernacles, in prayers implored the slayer of souls to afford them help against the sufferings of the people.”

“Then the sea, the tide upon the flood, with boiling waters swept me away to the land of the Finns. Never have I heard men tell of thee any such cruel deeds of war and dreadful work of swords.”

“He bade men prepare for him a good craft upon the waves, saying that over the waters where the swan rides he would seek that warrior-king, that prince renowned, since he had need of men.”

“Have it now and hold it, fairest of houses! Remember thy renown, show forth thy might and valour, keep watch against our foes!”

“Champions of the people of the Geats that good man had chosen from the boldest that he could find, and fifteen in all they sought now their timbered ship, while that warrior, skilled in the ways of the sea, led them to the margins of the land.”

“Then his corslet of iron things he doffed, and the helm from his head, and gave his jewelled sword, best of iron-wrought things, to his esquire, and bade him have care of his gear of battle. Then the brave man spake, Beowulf of the Geats, a speech of proud words, ere he climbed upon his bed: ‘No whit do I account myself in my warlike stature a man more despicable in deeds of battle than Grendel doth himself.”

“Men-at-arms bore to the bosom of the ship their bright harness, their cunning hear of war; they then, men on a glad voyage, thrust her forth with her well-joined timbers. Over the waves of the deep she went sped by the wind, sailing with foam at through most like uton a bird, until in due hour upon the second day her curving beak had made such way that those sailors saw the land, the cliffs beside the ocean gleaming, and sheer headlands and capes thrust far to sea.”

“Nay, we two shall this night reject the blade, if he dare have recourse to warfare without weapons, and then let the foreseeing God, the Holy Lord, adjudge the glory to whichever side him seemeth meet.”

“I long while have dwelt at the ends of the land, keeping watch over water, that in the land of the Danes no foeman might come harrying with raiding fleet.”

“Yet God granted them a victorious fortune in battle, even to those Geatish warriors, yea succour and aid, that they, through the prowess of one and through his single might, overcame their enemy.”

“Many a winter he endured ere in age he departed from his courts; full well doth every wise man remember him far and wide of the earth.”

“There came, in darkling night passing, a shadow walking.”

“Their fleet vessel remained now still, deep-bosomed ship it rode upon it hawser fast to the anchor. Figures of the boar shone above cheek-guards, adorned with gold, glittering, fire-tempered fierce and challenging war-mask kept guard over life.”

“Then a knight in proud array asked those men of battle concerning their lineage: ‘Whence bear ye your plated shields, your grey shirts of mail, your masked helms and throng of warlike shafts?”

“The door at once sprang back, barred with forgéd iron, when claws he laid on it. He wrenched then wide, baleful with raging heart, the gaping entrance of the house; then swift on the bright-patterned floor the demon paced. In angry mood he went, and from his eyes stood forth most like to flame unholy light. He in the house espied there many a man asleep, a throng on kinsmen side by side, a band of youthful knights. Then his heart laughed. He thought that he would sever, ere daylight came, dread slayer, for each one of these life from their flesh, since now such hope had chanced of feasting full.”

“Never have I seen so many men of outland folk more proud of bearing! I deem that in pride, not in the ways of banished men, nay, in greatness of heart ye have come seeking Hrothgar!”

“Straightway that master of evil deeds perceived that never had he met within this world in earth’s four corners on any other man a mightier gripe of hand.”

“Thereupon the worthiest of my people and wise men counseled me to come to thee, King Hrothgar; for they had learned the power of my body’s strength; they had themselves observed it, when I returned from the toils of my foes, earning their enmity, where five I bound, making desolate the race of monsters, and when I slew amid the waves by night the water-demons, enduring better need, evening the afflictions of the windloving Geats, destroying those hostile things – woe they had asked for.”

“Many a knight of stout heart went unto that lofty hall to see that marvel strange; so too the king himself from his bedchamber, guardian of hoards of rings renowned for his largesse, strode in majesty amid a great company, and with him the queen with her train of maidens paced that path unto the mead-hall.”

“Never aforetime had the Scyldings’ counselors foreseen that any among men could in any wide shatter it its goodliness adorned with ivory, nor dismember it with craft, unless the embrace of fire should engulf it in swathing smoke. Clamour new arose ever and anon. Dread fear came upon the northern Danes, upon each of those that from the wall heard the cries, the adversary of God singing his ghastly song, no chant of victory, the prisoner of hell bewailing his grievous hurt.”

“No need wilt thou have in burial to shroud my head, but he will hold me reddened with gore, if death takes me; a bloody corse will bear, will think to taste it, and departing alone will eat unpitying, staining the hollows of the moors. No need wilt thou have any lonter to care for my body’s sustenance!”

“Wherefore I expect for thee a yet worse encounter, though thou mayest in every place have proved valiant in the rush of battle and grim war, if thou darest all the nightlong hour nigh at hand to wait for Grendel.”

“The chief of those Geatish men had accomplished all his proud vaunt before the East Danes, and had healed moreover, all the woe and the tormenting sorrow that they had erewhile suffered and must of necessity endure, no little bitterness.”

“No man, friend nor foe, could dissuade you two from that venture fraught with woe, when with limbs ye rowed the sea. There ye embraced with your arms the streaming tide, measuring out the streets of the sea with swift play of hands, gliding over the ocean.”

“No grief for his departure from life felt any of those men who looked upon the trail of his inglorious flight, marking how sick at heart he had dragged his footsteps, bleeding out his life, from thence away defeated and death-doomed to the water-demons’ mere.”

“Therein doomed to die he plunged, and bereft of joys in his retreat amid the fens yielded up his life and heathen soul; there Hell received him. Thence the ancient men of the court, and many a young man too, fared back from their joyous journey riding from the mere upon their steeds in pride, knights upon horses white.”

Pingback: The Fall of Arthur | The Melbourne Review of Books