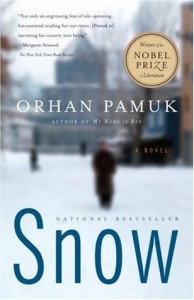

Orhan Pamuk (trans. Maureen Freely)

Faber and Faber (2004) ISBN 978-0-571-25823-9

Of Orhan Pamuk’s many gifts as a Nobel-awarded writer, one of the most fascinating is his ability to blur the lines between real life and fiction. Though the people he creates in his novels can speak and behave in ways that are surreal, in the context of his writing they are believable. This is a gift he shares with Haruki Murakami, a writer with whom I am more familiar, though the style and themes of Pamuk’s work is very different to Murakami’s. To qualify this observation I must add that I have thus far read only two and a half of Pamuk’s novels–The Museum of Innocence, which I didn’t particularly like; My Name is Red, which I promise I will one day finish; and Snow, which I review here. As in The Museum of Innocence, Pamuk is himself a character in Snow, which contributes to a feeling that the story, despite its surreal moments, might be true.

This edition of Snow was published as part of Faber and Faber’s ‘Revolutionary Fiction’ series, described as “celebrating provocative political fiction from around the world”. It centres upon the Turkish headscarf controversy, with which I have only passing familiarity, and the suicides of young women who have refused to remove their scarves and thus been banned by the Turkish secular state from attending school. A spate of such suicides occurred in the south-eastern city of Batman, but in the novel they occurred rather in the city of Kars, close to the Armenian border. “Kar” is the Turkish word for “snow”. This is played upon also in the name of the novel’s chief character, Ka.

Ka, an exiled and unproductive poet, travels to Kars to investigate the suicides of the “headscarf girls”. He also intends to reunite with a woman he knew in Istanbul, İpek, who he knows has recently divorced. Shortly after Ka arrives in the city, a blizzard forces the roads closed and a group of nationalists seize control of the city during a special television broadcast. Through the course of his investigation, both directed by curiosity and impelled by the requests of others, Ka becomes involved with the local branch of political Islamists and their leader, Blue. As matters escalate, Ka falls deeply in love with İpek and sets out to convince her to return with him to Germany. His writer’s block is also relieved after four years and he is able to author a number of poems, the titles of which are scattered through the novel, though the reader never sees them.

Kars is populated by a number cheerfully vicious characters, such as the newspaper editor who happily prints news a day before it happens, even to the extreme detriment of its subjects, and a headscarf girl who proudly admits to inciting a friend to suicide, albeit without believing she’d follow through. The story is punctuated with notes from the narrator, revealing the fates of several characters before events in the novel arrive at them. Several scenes are described as if from a distance, after the fact, for reasons which are eventually made clear. The novel is a supreme work of story-telling and of narrative structure.

In addition to its political themes of (to describe it very basically) secularism and Islamism, Snow investigates a number of other themes. The most obvious of these is the ‘hidden symmetries’ described by Ka in relation to several of his poetic works. There are symmetries scattered throughout the novel: the coup begins and ends with a stage performance; the novel begins with Ka arriving in Kars and ends with the narrator departing. There are subtle hints at the hypocrisy of both western and Islamic attitudes towards women’s bodies and sex in general: while Frankfurt has clearly visible sex shops and borderline pornographic advertisements, porn videos still must be concealed in an opaque plastic bag; Kars’ prostitutes and hardliner Blue’s sexual infidelities are concealed only for a short time.

I feel grossly underqualified to attempt a further thematic investigation of this book. It is the type of novel one can read again and again, to discover something new each time. However, I am not certain I would myself attempt to reread Snow.

Snow challenges assumptions that are often made about “headscarf girls” in Turkey and overseas. It is a rewarding, if sometimes troubling, novel. It is probably not for everyone, but I would nonetheless recommend it to anyone.