Memoir, politics

Crown

October 2014

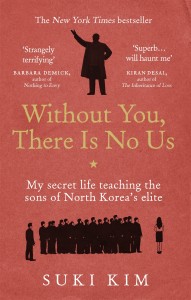

I first came across Suki Kim as a panellist at the exceedingly awkward “Inside North Korea” talk at this year’s Melbourne Writers Festival. I have written about this panel in more detail before, but Kim’s frustration at her co-panellists, and at the situation in and around North Korea generally, was as palpable there as it is in this book. Without You, There is No Us is a memoir of her time as a missionary English teacher at an elite university outside of Pyongyang. It is an incisive and self-reflective memoir.

I first came across Suki Kim as a panellist at the exceedingly awkward “Inside North Korea” talk at this year’s Melbourne Writers Festival. I have written about this panel in more detail before, but Kim’s frustration at her co-panellists, and at the situation in and around North Korea generally, was as palpable there as it is in this book. Without You, There is No Us is a memoir of her time as a missionary English teacher at an elite university outside of Pyongyang. It is an incisive and self-reflective memoir.

Kim seems highly knowledgeable about and yet mystified by the history and politics that have brought North Korea to this point. She reflects on her own links with North Korea, her mother having lost an older brother during the Korean War, who was conscripted into the North Korean army and never heard from by the family again. Kim creates a sense that she is aware of just how narrow things were for her family, and for many Korean families. That one small twist of fate has meant the difference between living in relative freedom and material comfort in South Korea, and living a life of poverty under the all-pervasive surveillance state of North Korea.

The story starts with these reflections, and quickly moves into her experiences over two semesters at the Pyongyang University of Science and Technology (PUST). She quickly comes to love her students, but is also sharply aware that she cannot trust them. Though already experienced from previous visits with being constantly monitored, she soon finds the nature of life in PUST overwhelming. Every lesson plan, even down to games, must be approved according to arbitrary and often puzzling state and school requirements. Every conversation that strays from certain set topics is fraught with danger. For it is not only Kim’s stay in North Korea that is at risk if she reveals too much about life on the outside; it is her student’s very lives. In this book, she has taken care to blur student’s identities to protect them from potential repercussions even of the seemingly minor questions they ask of her, and of the hints some of them seem to have of how restrictive, how extraordinary*, their lives are.

Kim is certainly jaded not only by the regime but by the international media’s treatment of it, though maintains fiercely sympathetic with the plight of the North Korean people. There are several scenes when Kim does manage a glimpse behind the elaborate veil that is constructed for foreigners. Some of these scenes felt as if they must have been exaggerated as well as blurred, but I can’t say for sure. Perhaps I would simply like to hope they are exaggerated. Kim can only speculate about the lives led by North Korea’s myriad poor, but what she does describe speaks of the most terrible hardship.

Without You, There is No Us is a story of tentative optimism about moulding young minds away from their oppressive state, being smothered by the inescapable machinery of control. Though it ends with a renewed hope in the potential for change, as Kim Jong-Il’s death is announced, history has shown that Kim Jong-Un’s regime is as unrelenting as ever.

Kim’s search for truth in North Korea is deflected at every turn. Even moments that might hint at candidness, at unveiling, are quickly joked away, quickly tainted with doubt. Kim is uncertain her students even really know the difference between truth and lies. The extreme level to which they have been brainwashed is perhaps the most harrowing thing about the novel. Even when they express doubts, they quickly suppress them; even when Kim is able to reveal her own life, the students pretend nothing has happened.

The memoir is written with an expert combination of journalism, history both in the macro and family sense, and personal reflection. Kim’s language is engaging and for the most part unexaggerated. She does not try to transform herself into a heroine and at times, mostly when she was mooning about her lover back in New York, I found her irritating. While that was not likely Kim’s intention, the honesty with which she portrays herself is an offer to the reader. It is to tell us we can believe what she says about this most untrustworthy of places.

* Both in an global sense and within North Korea. PUST students were almost all from elite and well off families.