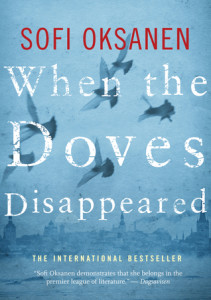

WHEN THE DOVES DISAPPEARED

WHEN THE DOVES DISAPPEARED

Sofi Oksanen, translated by Lola M. Rogers

Atlantic Books, May 2015, RRP $27.99

When the Doves Disappeared is a thoughtful glimpse into Estonian life during occupation by Nazi Germany, and the subsequent USSR rule. It is a study in the meaning of political conviction; passion; loyalty; and love, amongst many other things. Estonian-Finnish poet Sofi Oksanen’s second novel, it is both espionage thriller and literary reflection, with a gripping plot, elegant language, and carefully crafted, deeply flawed characters.

The story starts in 1941 with cousins Roland and Edgar, two soldiers in the Estonian Army, fighting the Soviet occupation as the Nazis approach. Edgar is unhappily married to Juudit, who herself watches the incoming Germans with apprehension and hope. Roland is engaged to Rosalie and looks forward to his coming marriage. While Edgar believes the Germans will bring liberation from the Soviets, giving Estonia its independence, Roland has his doubts. After Rosalie dies unexpectedly, Roland heads into the underground to fight for a truly independent Estonia. Meanwhile, liberated from one another by the chaos of war, Edgar and Juudit separately go about inveigling themselves with the Germans.

As the story progresses, we are taken through the tumult of the Second World War in Estonia, as well as Edgar’s life in the 1960s as a Party member working to track down Roland. This broken up chronology and use of multiple points of view serves the novel excellently, creating a genuine sense of mystery and tension. This is important in a historical novel about a topic such as World War Two. The reader is likely aware of the inevitable German defeat by the Soviets and the subsumption of Estonia into the USSR. Oksanen keeps a good balance of answering and opening new questions. The conclusion in this regard is also satisfying, leaving enough open that it does not feel too neat or contrived.

Another of Oksanen’s strengths is in building atmosphere. She fills the reader with a genuine sense of what living under Nazi occupation and Soviet political repression might have been like; the inability to trust even one’s closest friends and lovers; shortages in food and material goods; the knowledge that some people have simply disappeared, and will likely never be found. Nazi war crimes in the region are subtly escalated as the war turns against them.

What I didn’t like about this novel was its characters. Of course, Juudit is not meant to be particularly likeable, and Edgar is a despicable person. Roland is probably the character I liked best, but we see very little of him after the first parts. Perhaps Oksanen is trying to tell us that these kinds of people are the ones who survive during miserable times. It is obvious from the first 1960s chapters that Roland has joined the ranks of the disappeared, along with his dreams of a free Estonia. And it is not necessary for a reader to like characters to care about what happens to them or to recognise them as well-crafted characters. This, at least, is no criticism of Oksanen; she has created believable characters who provoke emotional responses.

My main issue, however, is the characterisation of Edgar as possibly (probably) homosexual*. Mainly because his closeted homosexuality appears to be another element of his conniving and self-serving personality. I don’t mean to imply that all homosexual characters in any book should not be any of those things, but when combined with Edgar’s weakness against any real challenge, emotional coldness, and implied effeminiteness it becomes a problem by mirroring vindictive stereotypes. The way Edgar is written implies he is such a nasty human being because he is gay, rather than in addition to being gay.

I found this an interesting read. If you are a fan of 20th century history or of espionage and political thrillers, I would recommend When the Doves Disappeared as a compelling read. And though the book is targetted at fans of John Le Carré and Stieg Larsson because of its plot, those of more high-brow literary tastes will find a gently handled, lyrical novel with a depth of themes to explore.

*I did suspect asexual at first. This would certainly be novel, since asexuality receives so very little representation. However, I think this reading also poses problems, given the implication that a person who does not require sexual intimacy with another must lack empathy or the capacity for love and genuine friendship.