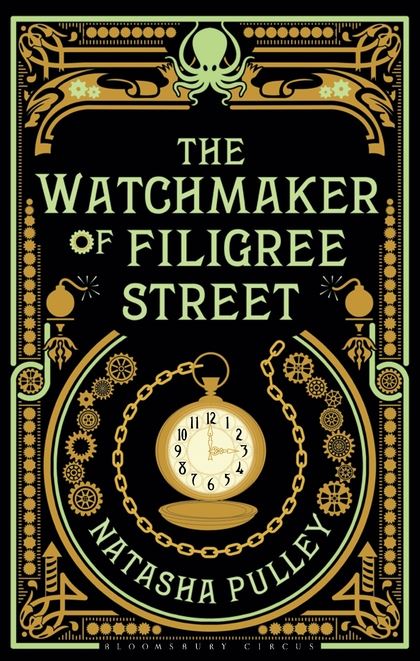

THE WATCHMAKER OF FILIGREE STREET

THE WATCHMAKER OF FILIGREE STREET

Bloomsbury Circus, RRP$29.99

July 2015

For those of you who were hurtling toward adulthood in the mid-90s listening to Blur’s The Great Escape over and over again, you may recall the quiet melancholy tune sandwiched between the poppier sounds of ‘It Could Be You’ and ‘Globe Alone’. It went a little something like this:

“Ernold Same awoke from the same dream in the same bed at the same time

Looked in the same mirror made the same frown

And felt the same way as he did every day

Then Ernold Same caught the same train at the same station

Sat in the same seat with the same nasty stain next to same old what’s his name

On his way to the same place to do the same thing again and again and again

Poor old Ernold Same”

Thaniel Steepleton is a synaesthete and a megalomechanophobe but he is not Ernold Same. Not yet. Though one can’t help but think his life could very well head that way. That is if he doesn’t get blown up by the Fenians first.

Thaniel’s life is a humdrum affair. It consists of waking up in his tiny flat in a boarding house near the Thames, trudging to work in the telegraphy department of the Home Office, and then trudging home again in time to go to sleep and start all over again the next morning. Of course the threat of government buildings being blown up when you work in a government building tends to create a little upset in an otherwise routine existence. And then of course there’s mysterious gold watches turning up in your room…

[insert sound of squealing brakes here]

Let’s talk about steampunk for a moment. Is the definition free and loose? What I assume, from the name, is that steam power must be central to the way technology runs. If a book is set in Victorian London and it is just Victorian London with no dirigibles in sight but a Victorian London that contains an extremely talented watchmaker, does that make a book steampunk? I’d argue for the negative.

If I had to categorise it, which I suppose I must though I am dragged to this discriminatory nadir of the modern age kicking and biting, I’d say The Watchmaker of Filigree Street was historical fantasy—clock-punk if I’m pushed but probably more clock-jazz or clock-sonata to be more accurate. Though in protestation I find this micro-labelling about as healthy as gendered toys—I shan’t digress further on the topic lest I implode.

So where were we? Ah yes. A mysterious golden watch in Thaniel’s room. In this alternate, slightly more clockworky London of late 1883, a threat to blow up all the public buildings in six months’ time brings about all manner of trepidation and preparation—mainly of wills. When the watch saves Thaniel’s life, suspicions are aroused and the watch and bomb maker must be found. Thaniel must attempt a covert investigation of Keita Mori, the greatest watchmaker in London. He soon finds himself intrigued by the watchmaker’s quiet way of life, by his corner of little Japan in the middle of London, and by his pet Katsu.*

Meanwhile in Cambridge, brilliant physicist Grace Carrow is about to take a fall from promising researcher to society heiress. Sadly, the only way Grace can continue her research into the existence of ether is to get her hands on her money. And the only way she can do that is by finding herself a husband.

The story plays expertly between Mori’s old life in Japan and in London, Thaniel’s moral dilemma of spying on Mori, and Grace’s quest to continue her experiments by marrying. Amid all this hullabaloo, Mori finds a way to reunite Thaniel with music—a love he gave up to support his widowed sister.

The Watchmaker of Filigree Street is an utterly gorgeous and clever debut from Natasha Pulley. From the foggy greyness of old London to the upheaval of Meiji Era Japan, Pulley evokes a sense of place that leaps off the page straight into the mind cinema. The book drew me in like the gentlest of whirlpools, eliciting all manner of emotions—tension, excitement, wonder, squee—as all good mysteries should. And that is what this is—a mystery, a love story, and a damn fine adventure.

I find it the rare book that leaves me both eager and reluctant to reach the end. Eager for answers, reluctant for it to be over. We are left guessing who the actual bad guy is until we are finally left wondering if there ever was one in the first place. Perhaps the only bad guy is the spectre of Ernold Same hanging over all our lives.

“Oh Ernold Same, his world stays the same

Today will always be tomorrow

Poor Ernold Same, he’s getting that feeling once again

Nothing, nothing will change tomorrow”

*Seriously, I want a Katsu. Katsu is possibly the coolest thing ever.