This is the fourth instalment in my reread of Dorothea Brande’s remarkable 1934 book, Becoming a Writer. You can find part one here. In part one Dorothea Brande described the four key difficulties that prevent a person from writing. In the second chapter, she takes a closer look at what functional, professional writers are (generally speaking) like as a group. In part three, Dorothea takes a closer look at the advantages of splitting yourself into two people in your writing life.

This is the fourth instalment in my reread of Dorothea Brande’s remarkable 1934 book, Becoming a Writer. You can find part one here. In part one Dorothea Brande described the four key difficulties that prevent a person from writing. In the second chapter, she takes a closer look at what functional, professional writers are (generally speaking) like as a group. In part three, Dorothea takes a closer look at the advantages of splitting yourself into two people in your writing life.

In the fourth chapter – subtitled ‘Interlude’ – we have a short discussion about advice and how to take it (or not).

INTERLUDE: ON TAKING ADVICE

I’m going to start this off with my own experience workshopping. Especially when a person starts workshopping writing, they tend to fall into two camps, both of them a bit self-undermining:

1) Take nothing on board: The first of these advice types is the one where the writer really just wanted unadulterated praise, and on receiving criticism they react with a sort of ‘ you don’t know what you’re talking about’ ire and refuses to absorb (or perhaps even read) the criticism.

2) Take everything on board: This is much more typical of a new writer who is full of anxious nerves and has difficulty believing that their particular style and voice might not suit everyone, but might still have merit. This tends to manifest in a sort of desperate ‘absorb all edits’ approach, where every last comment is integrated into the revised draft, sometimes rendering it into a voiceless and blandness pallor.

I always advise writers to take my crits with a grain of salt if I am critiquing and that I reserve the right to be totally wrong about something I’ve said. I do this because I think that Camp 1 will come around to listening to others only after a series of rejections of publishers and Camp 2 are the ones who are really in danger of just upping and stopping writing altogether if they feel overwhelmed by too much negative feedback.

Okay. So, let’s look at the chapter. Dorothea identifies a completely different problem, one where a new writer is so zealous about exercises and advice that they might exhaust themselves right out. Well, that is a problem too. It’s not one I’ve encountered a lot myself I suppose, but it does exist. Her advice is to be careful about levelling too much personal energy at a task that requires really a fraction of what is needed. This makes sense, although I’d have phrased it differently, which is to think about which of your tasks have the highest potential pay-off (is it writing a new short story, a chapter or doing those edits you’ve been putting off) and adjusting your energy to the task’s potential return. Certainly if you are prone to over-exertion and exhaustion, it is very good advice to keep in mind that you don’t need to put endless time and effort into what may be in effect relatively unrewarding tasks.

The Slow, Dead Heave of the Will

Ah – and now we reach on of the parts of this book that first made me wonder how Dorothea Brande is not a household name outside of writing advice. Dorothea argues that the changing of habits can be better achieved not by the cold and remorseless application of willpower, but through use of imagination, if not always, then at least, give imagination a go first. It’ll tax you a whole lot less.

We have the insight that old habits are hard to break free of, and after a couple days of focused will, you are likely to suddenly ‘discover’ a lot of reasons why the new approach isn’t working. We’d now call this post-hoc rationalisation – you unconscious has already decided you want to give up. You’re now just hunting for an excuse that is good enough to allow you to escape with some sense of self-esteem intact.

The next part is an exercise to demonstrate this. Now, I didn’t do this exercise the first time around, largely because I was mostly reading on a train at the time and it requires a desk and the exercise was mostly just to prove that the unconscious really does exist. I’m already sold on the existence of the unconscious but I’ll explain the exercise here in case you want to try it.

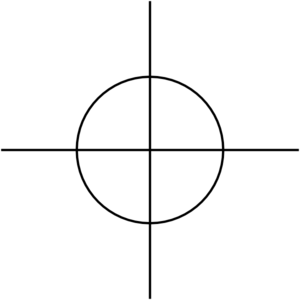

- Draw a circle with two perpendicular lines through it as if you were drawing a crosshair (example inserted below)

- Tie a key or ring to a 12 cm (about 4 in) piece of string

- Hold the object over the crosshair like a pendulum

- First let your vision run around the circle clockwise, around and around. Ignore the pendulum as much as possible. Don’t think about it. You’ll find the pendulum (probably) starts moving without your voluntary control. it just follows you imagination or unconscious thoughts

- Try it anti-clockwise. Try running your focus up and down the vertical line. Try running your focus left and right along the horizontal line.

The point of this is to convince the would-be writer not to try and force exercises or changes of habit, but rather to spend some time imagining the direction you want to move in or the outcome you want. This is a very early (1934!) anticipation of ideas like positive visualisation and writing affirmations each night before going to bed – both of which work to varying degrees for different people but are worth trying.

That’s the end of this short chapter. The next chapter is on Harnessing the unconscious.